This first in a two-part series reviews patient assessment, red flags, and pharmacologic agents.

Takeaways:

- Registered nurses providing moderate procedural sedation and analgesia must demonstrate clinical competency and a working knowledge of their state board of nursing requirements.

- Propofol is not pharmacologically reversible when used in the sedation setting.

Infusion therapy: A model for safe practice in the home setting

An overview of neuraxial anesthesia

Preventing high-alert medication errors in hospital patients

IN 1978, Bennett first described the clinical effects associated with I.V. conscious sedation and its impact on dental practice. Revised clinical practice guidelines have replaced the word conscious with moderate to address differences that occur within the continuum of sedation. The terms moderate sedation and procedural sedation are now used interchangeably.

Over the last several decades, procedural sedation and analgesia for surgical, therapeutic, and diagnostic procedures has gained widespread popularity. The rationale for its proliferation includes medical technology that allows providers to treat patients with minimally invasive procedures and techniques that no longer confine them to traditional perioperative environments.

With healthcare’s focus on cost and efficiency, procedural sedation and analgesia administered by non-anesthesia personnel provides an alternative for many procedures. As a result, the demand for competent sedation nursing care has increased, and many registered nurses have assumed sedation subspecialty roles in gastroenterology settings, emergency departments, cardiac catheterization labs, operating rooms, fertility clinics, and interventional radiology settings.

Part 1 of this two-part series reviews the sedation continuum, the goals of procedural sedation and analgesia, presedation patient assessment, and the relevant pharmacologic agents.

The sedation continuum

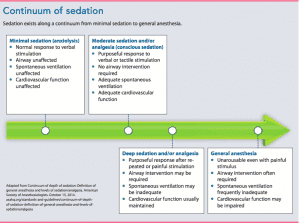

Sedation exists along a continuum that progresses from a state of minimal sedation to general anesthesia. (See Continuum of sedation.) Procedural sedation and analgesia is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. (Note that reflex withdrawal from a painful stimulus is not considered a purposeful response.) No interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, spontaneous ventilation is adequate, and cardiovascular function is supported.

Goals and objectives

The goals of procedural sedation and analgesia vary based on procedural requirements, provider preferences, and the sedation technique. Regardless of these variables, goals include administering the lowest dose of medication to:

- maintain patient safety and welfare

- minimize physical pain and discomfort

- control anxiety, minimize psychological trauma, and maximize amnesia

- control behavior and movement to allow safe performance of the procedure.

Presedation patient assessment

The clinician who will administer the sedation should conduct the presedation patient assessment in an unhurried atmosphere so he or she can gather patient data, order laboratory tests, and implement a sedation plan of care. During the assessment, the clinician seeks to identify patient risk factors that may lead to complications and ensure that the patient is in the best physical condition for the planned procedure.

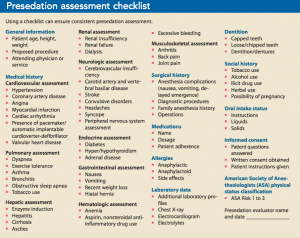

To ensure consistent, thorough presedation assessment, many clinicians follow a prescribed assessment format. (See Presedation assessment checklist.) Joint Commission standards and elements of performance require that patients be reevaluated immediately (moments) before sedation administration.

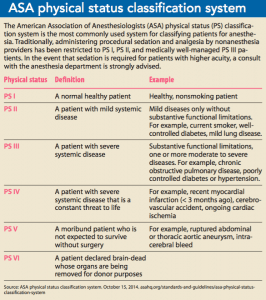

After the presedation assessment, the clinician assigns the patient a physical status classification. The most commonly accepted classification system, first developed in 1940 by a committee of the American Society of Anesthetists (now the American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA]), assigns a category based on the assessment findings. (See ASA physical status classification system.)

OSA: A red flag

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a pulmonary disorder of significant concern for sedation providers. It affects up to 17% of middle-aged women and 22% of middle-aged men, but less than 15% of those have been diagnosed. OSA is a disorder of the upper airway at the level of the pharynx. It leads to fragmented sleep, arterial hypoxemia, hypercarbia, polycythemia, systemic and pulmonary hypertension, and right ventricular failure.

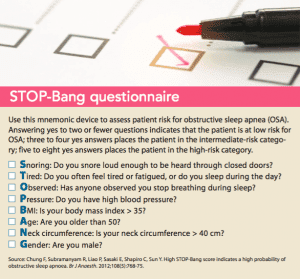

The most common OSA signs and symptoms include morning headache, hypertension, stroke, ischemic heart disease, cognitive dysfunction, and overwhelming somnolence during normal working hours. The STOP-Bang questionnaire is a validated screening tool used to identify a patient’s risk for OSA. (See STOP-Bang questionnaire.)

Scheduling patients with OSA early in the morning for procedures requiring sedation and analgesia allows for a lengthier recovery and assessment period to identify post-procedure respiratory complications (apnea, hypopnea). Clinical management includes careful assessment of the patient’s airway before beginning the procedure and placement of the patient’s continuous positive airway pressure, bilevel positive airway pressure, or adaptive servo ventilation device immediately after the procedure. Oxygen may be beneficial during and after the procedure. To avoid deep sedative states or general anesthesia, titrate sedative drugs to clinical effect. Patients with OSA are highly sensitive to all central nervous system depressants. Even minimal doses increase the potential for increased airway obstruction or apnea. Practitioner interventions to effectively manage airway obstruction include chin-lift/jaw-thrust, airway insertion, and use of a bag-valve-mask device.

Preprocedure oral intake

The clinician should provide the patient with preprocedure fasting guidelines. Historically, patients have been instructed to have nothing to eat or drink after midnight the night before the procedure to decrease the risk of gastric acid aspiration. However, these guidelines don’t address the:

- time of the procedure

- time the patient went to bed the night before the procedure

- variability associated with gastric emptying for solids and liquids.

Failure to address these variables can lead to dehydration, hypoglycemia, hypovolemia, increased irritability, enhanced preoperative anxiety, thirst, hunger, and headaches.

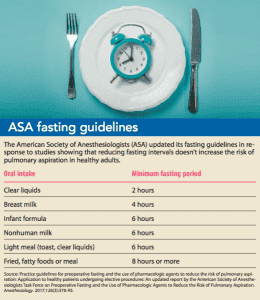

The ASA recently updated its practice guidelines for preoperative fasting based on studies that showed a reduced fasting interval did not increase the risk of pulmonary aspiration in normal, healthy individuals. (See ASA fasting guidelines.)

Pharmacologic agents

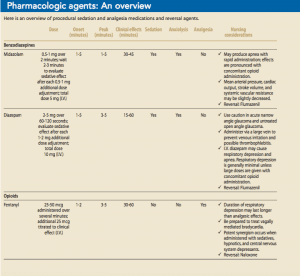

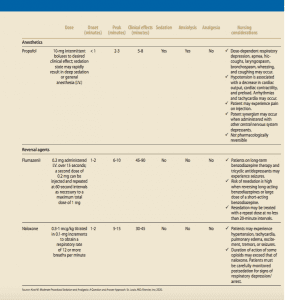

Combinations of carefully titrated sedative, analgesic, and hypnotic medications alter a patient’s level of consciousness and enhance cooperation. However, sedative and analgesic medications also may produce profound synergistic effects, which may lead to deep sedation or general anesthesia. Successfully producing a sedate, analgesic state and minimizing complications (respiratory distress, cardiovascular depression, and hypoxemia) requires an understanding of these medications as well as the reversal agents that may be needed if the level of sedation becomes deeper than intended. (See Pharmacologic agents: An overview.)

Note that benzodiazepines and narcotics are pharmacologically reversible, but propofol is not and may produce rapid, unpredictable effects, including respiratory arrest.

Propofol

Several professional organizations— including the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society for Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates— have endorsed nonanesthesiologist or nurse-administered propofol administration. However, the Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) notes that propofol should be administered only by “persons trained in administering general anesthesia and not involved in the conduct of the surgical/diagnostic procedure.”

Here’s some background on the status of propofol administration by nonanesthesia providers:

- Reports of adverse patient events have been connected to non-anesthesia provider propofol administration. Over a decade ago, the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System received more than 100 reports in which propofol administration in untrained hands resulted in adverse patient events. Sixteen percent of those reports were classified as serious events, including four patient deaths.

- In 2009, Rex and colleagues reported that propofol is known to cause hypoventilation, hypotension, and bradycardia relatively frequently, but they posit that severe adverse events are rare.

In 2005, the American College of Gastroenterology petitioned the FDA to remove warnings about who can administer propofol from its package labeling. In a 2010 letter, the FDA denied the petition and noted that the warning “should help ensure that propofol is used safely.” Nonanesthesia providers who administer or monitor patients receiving propofol must recognize that the Institute of Patient Safety recognizes it as a high-risk medication. Propofol is not reversible and may produce rapid, unpredictable effects, including respiratory arrest. The prescribing clinician and nonanesthesia provider administering the sedation and monitoring the patient should possess advanced airway-management skills, demonstrate proficiency in managing cardiovascular complications, and recognize that propofol can induce deep sedative states and general anesthesia. Before administering this sedative, nurses should check their state board of nursing to ensure this care is within their scope of practice.

Be prepared

Preparing the patient and care team for procedural sedation and analgesia requires a thorough patient assessment, awareness of potential red flags, and a firm grasp of pharmacologic and reversal agents. Learn about airway management, procedural monitoring, and postsedation care in part 2 of this two-part series.

Selected references

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):1004-17.

Amornyotin S. Registered nurse-administered sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedure. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7(8):769-76.

Continuum of depth of sedation: Definition of general anesthesia and levels of sedation/analgesia. American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2014. asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/continuum-of-depth-of-sedation-definition-of-general-anesthesia-and-levels-of-sedationanalgesia

Bennett CR. Conscious Sedation in Dental Practice. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1978.

Docket No. FDA-2005-P-0059. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. August 11, 2010. digestivehealth.net/images/FDA-2005-P-0059-0080_1_.pdf

Farney RJ, Walker BS, Farney RM, Snow GL, Walker JM. The STOP-Bang equivalent model and prediction of severity of obstructive sleep apnea: Relation to polysomnographic measurements of the apnea/hypopnea index. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(5):459–65B.

Franklin KA, Lindberg E. Obstructive sleep apnea is a common disorder in the population—A review on the epidemiology of sleep apnea. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(8):1311-22.

Practice guidelines for moderate procedural sedation and analgesia 2018: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Dental Association, American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists, and Society of Interventional Radiology. Anesthesiology. 2018:128(3):437-79.

Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):376-93.

8 Comments.

Very informative

Very informative

Good artical

Good info

Thank you for the awareness

Thank you for reading!

nice review needs more depth on airway assessment

Good article!